Understanding Cubital Tunnel Syndrome

What is Cubital Tunnel Syndrome?

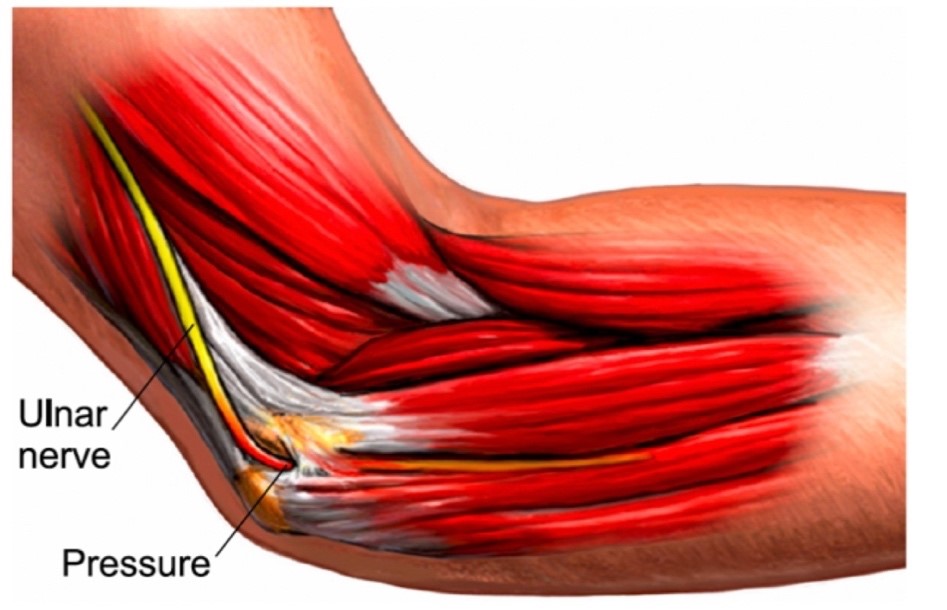

Cubital tunnel syndrome occurs when the ulnar nerve, located in a narrow passageway on the inside of the elbow (commonly referred to as the “funny bone”), becomes compressed or irritated. The ulnar nerve is responsible for providing sensation to the little finger and part of the ring finger, as well as controlling small muscles in the hand.

What Causes Cubital Tunnel Syndrome?

In most cases, the exact cause is unknown, but the condition can develop due to narrowing of the tunnel from arthritis in the elbow joint or from previous injuries. Many patients experience symptoms from leaning on their elbows or from prolonged pressure on the ulnar nerve, such as when sitting at a desk for extended periods while using a computer.

What Are the Symptoms?

The earliest signs of cubital tunnel syndrome are numbness or tingling in the little and ring fingers, which can be intermittent but may become constant over time. Symptoms are often triggered by leaning on the elbow or keeping it bent for long periods (such as when holding a phone). Sleeping with the elbow bent can also worsen the symptoms.

In the later stages, the numbness becomes persistent, and weakness in the hand may develop. Severe cases may lead to visible muscle wasting, particularly between the thumb and index finger, along with a noticeable loss of strength and dexterity.

What is the Natural Course of the Condition?

Cubital tunnel syndrome often comes and goes, and in many cases, the symptoms resolve on their own with simple changes, such as avoiding pressure on the elbow and preventing the elbow from being held in a fully bent position for extended periods.

How is it Treated?

In the early stages, the main treatment involves activity modification. This includes adjusting the workstation setup to avoid prolonged elbow flexion and pressure on the nerve. For example, computer keyboards should be placed at the edge of the desk, and workstation chairs should avoid armrests that place pressure on the elbow.

If non-surgical treatments are ineffective, or if the condition becomes severe, surgery may be needed to decompress the nerve. The primary goal of surgery is to prevent further muscle weakness and wasting, though it can also improve numbness. During surgery, a small incision is made over the nerve at the elbow, and the thick fibrous tissue pressing on the nerve is removed, alleviating the pressure.

What is the Outcome of Treatment?

The outcome depends on the severity of the nerve compression. Numbness often improves, though the recovery can be slow. While surgery usually prevents further muscle weakness, improvement in muscle strength is gradual and may not be fully restored.

In mild cases, symptoms often resolve completely, but in more severe cases, the recovery of nerve function may be less predictable. Overall, about 85% of patients report satisfaction one year after surgery.